State in Functional Requirements

01 May 2016In a previous note I discussed software functional requirements, and talked about how going back to the basics of software and requirements eventually led me to decide that the Behavior-Driven Development community’s Given/When/Then structure was a good way to define requirements. In that note I talked about the way that “shall” statements, as they’re often used, provide a description of a “timeless truth” about the system (“Aristotle is human”), rather than a description of a dynamic change in the system (“when he gets hungry Aristotle stops thinking deep thoughts and starts eating”). But the purpose of most software (at least the stuff that doesn’t exist just to solve numerical problems) is to be dynamic, so to define its requirements we need a way to describe behavior. In this note I want to explore that notion of describing the behavioral requirements for dynamic systems in a little more depth.

Be dynamic!

The classical way to describe dynamic systems, at least since the time of Newton, is to use one or more differential equations. Maybe you remember differential equations from your calculus classes. Or maybe you’ve suppressed the memory. Anyway, the basic concept of a differential equation is to describe the rate of change of one or more quantities as a function of the current value of those quantities. Your suppressed memories of calculus class may include equations like:

dy/dt = 0.5 y

The differential equation is a concept that works great for the kind of systems Newton was interested in (continuously variable quantities in physical systems), but isn’t quite so meaningful for describing computational behaviors (which mostly involve discretely varying inputs and outputs). And yet…

Differential equations are really just another form of Given/When/Then statement:

- Given the value of

yis some number- When an infinitesimal interval of time

dtpasses- Then the value of

ybecomesy + (0.5 y dt)

The Given/When/Then structure specifies a state transition: the Given describes the starting state, the When defines the trigger for the transition, and the Then describes the end state. In the case of physical systems, the state of the system changes in response to the passage of time. In the case of computational systems we often abstract from the passage of time, and focus on how the state of the system changes in response to input events. Many of the formalisms that have been developed for specifying software (e.g., Z, the B-Method, or SCR) are structured mathematical ways of expressing state transitions.

State what the system should do

Ok, so describing dynamic systems (or behavior) is all about describing state transitions, and that’s what a Given/When/Then statement does. Which, if you’ve got any kind of background in computer science, probably has you thinking about state machines. It certainly led the ever-insightful Bob Martin to think about state machines, as he explained way back in 2008 in a post about BDD. So why bother with Given/When/Then? Why not just draw a state machine and call the requirements done?

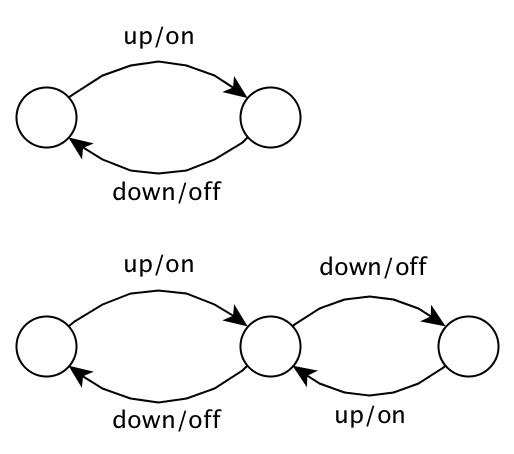

The tricky thing about a state machine, at least in my opinion, is that it starts to look a lot more like design than it does requirements. With a state machine, we’re not just describing what behavior we expect. By defining states in a state machine we’re describing how we expect that behavior to be produced. I mean, yes, a state machine describes a set of behaviors. But the problem is that you can have several different state machines that describe the same behaviors. For a ridiculously trivial example of this situation consider the following two state machines, which both describe the behavior of a switch.

Which one of these represents “the required behavior”? Both can produce infinite sequences of alternating up/on and down/off events. From the perspective of an external observer (i.e., someone who cares about requirements but not implementation) they’re indistinguishable. The difference between the two state machines is a design detail, not a matter of requirements. And that’s a simple example! Now imagine the possible state machines defining the behavior for a real system. How can you tell whether or not there are extraneous states that aren’t actually required to produce the desired behavior, but happen to be there because that’s how the person writing the requirements thought about the system?

Actually, theoretical computer scientists have developed an entire spectrum of ways to classify observable equivalences between state machines, with the distinctions between different equivalences being dependent on what kind of observations the external observer is able to make. Which could be handy if you wanted to be able to “refactor” a state machine into a simpler design that produced behavior equivalent to whatever system you started with. If you’re interested in such things, a quick search of the web for terms like “trace equivalence”, “failures refinement”, or “bisimulation” will yield all sorts of fascinating results. But I digress…

When I write requirements, then I know what to design

I’m going to assume that you’re more interested in practical specification of software requirements than you are in theoretical computer science. Which is why I think you’ll (still) find Given/When/Then statements a better choice for defining functional requirements than a state machine.

The nice thing about Given/When/Then is that it doesn’t actually define a state machine, because it doesn’t define states. The Given and Then parts say what must be true about a state (ideally in terms of observable phenomena that characterize the state), without necessarily specifying that a particular state must exist. A collection of Given/When/Then statements together define a set of behaviors that could be produced by any of several different state machines. Which is really the point of this whole note. Requirements shouldn’t be defining states. Part of the design process is figuring out which state machine is the best choice for creating the required behavior, while also fulfilling various design principles and architectural constraints.