Why Think About Software Architecture?

15 Oct 2017Why do we structure a software design the way we do?

For that matter, why do we structure a design at all?

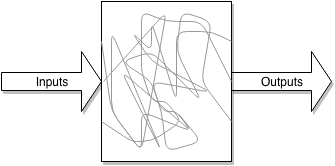

If all we cared about was the mapping from software inputs to software outputs, then an internal design that looked liked spaghetti would be just fine.

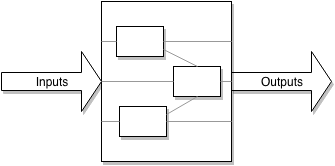

Of course, we do impose a structure on our designs. We split things into functions, objects, and modules. But why? Clearly there’s more at work here than just input/output requirements.

The structure of your design, or its “architecture”, consists of the high-level components you build the software from (modules, libraries, databases, etc.), and the way that those components are connected to each other. Your software will have an architecture, whether you plan it or not. Maybe it’s worth giving that architecture some conscious thought.

But why?

Think back to your last software development project. Did you think about architecture at all? If you did, can you explain why you chose the components that you did?

If you’re like a lot of software developers, you may have broken your design down into components that are responsible for separate “major functions”.

Perhaps you tried to “hide” key design decisions within individual components, which is characteristic of modern object-oriented design and is the goal of many design patterns.

You probably also used a bunch of off-the-shelf components (libraries or frameworks, perhaps even entire third-party applications).

And maybe, if you thought about architecture, you used one of the classic architectural patterns: layers, pipes-and-filters, a blackboard.

No, really, why?

But why did you do things that way?

If you reflect on the architectural decisions you made I think you’ll find that, even if you didn’t think about it consciously at the time, a lot of your design was driven by what are sometimes colloquially called “-ilities”: the quality attributes of your system that you’re trying to achieve along with meeting the functional requirements.

Much of your architecture was probably driven by a concern for understandability. A decomposition into subsystems and modules isn’t necessary to meet the functional requirements. But decomposing things that way makes it easier to understand how and why individual requirements are met. It’s certainly easier to understand than spaghetti.

Hiding design decisions is an approach advocated in David Parnas’ seminal paper on software design, “On the Criteria to be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules”, in which he argues against functional decomposition and proposes using changeability as a criterion for structuring a design. Design for changeability is also baked into the Bob Martin’s famous SOLID principles of software design.

Using well-known architectural patterns inevitably enhances understandability, since anyone looking at the system will know what to expect. Individual architectural patterns also support other qualities. For example, a layered architecture supports changeability through hiding design decisions within layers.

And what about those off-the-shelf components you used? Why not write everything from scratch? You were probably motivated by things like the affordability of the required work versus the cost of the components, and the feasibility of meeting your schedule.

It’s all about the -ilities

Seeing architecture as being driven by quality attributes (the “-ilities”) is a viewpoint I first encountered in the book Software Architecture in Practice. There’s a whole body of work on this approach by the Software Engineering Institute, under the name “Attribute-Driven Design” (ADD). You don’t need to apply the whole ADD methodology to get some value out of thinking in terms of quality attributes though. Simply looking at your software architecture from the perspective of quality attributes, instead of just using a design or architectural principles that someone told you were “good”, makes you stop and consider why your architecture looks the way it does.

Is a layered architecture always the best choice? It depends on what quality attributes you’re really interested in. Maybe it makes sense to violate the layering to support other quality attributes (a performance-related quality, perhaps). By thinking about quality attributes you can make the decision to violate layering in a principled way (and explain in your rationale in your architecture documentation).

What about your use of off-the-shelf components? How did you make your “make vs buy” decision? Were there other criteria in play aside from affordability? Have you considered maintainability or interoperability? Again, you can approach the make/buy decision in a principled way.

Perhaps most importantly, looking at the architecture from the perspective of quality attributes can help you think about the quality attributes you should consider but haven’t yet. How important is reliability to your system? What about scalability? Have you given any thought to preserving confidentiality (a key security property)? What about the usability of your interface? Is there something on Wikipedia’s list of system quality attributes that you should be considering?

Think about architecture so that you get an architecture you’ve thought about

So, next time you look at the architecture of your software (either a new design, or your existing project), ask yourself “what are the key quality attributes here?” You’ll have a much better idea of why your software is structured the way it is. And you may just find some ways to make a better architecture.